tide tables

For shore anglers, mobile phones are rapidly making the traditional tide table booklet very much an old school thing. Regardless of that, how the tides work and the everyday language used to describe them remains timeless. Tide describes the vertical movement of the sea; high, low, rising and falling.

The effect of the tide upon the seashore is described in horizontal terms; flooding, ebbing, coming in and going out.

A tidal stream, current, flow or rip is the exceptional movement of the sea caused by the tide that could affect the safety of swimmers or passage of sea vessels.

the tidal bulge

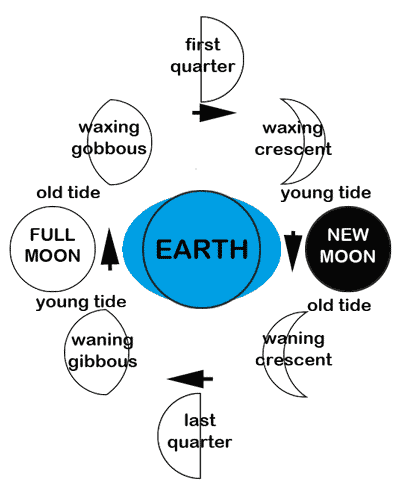

The times of high and low tide are astronomical predictions based  upon the gravitational pull of the moon and sun upon the ocean. This creates a tidal bulge that travels from the Atlantic into the Irish Sea and into the English Channel. Regardless of it being a spring or neap tide, when the peak of the tidal bulge (high tide) has progressed up the English Channel to Dover, the following trough (low tide) will be around Falmouth. Every month the full and new moon align with the sun maximising their gravitational pull, creating spring tides. As they move out of alignment the gravitational pull is reduced, creating a period of neap tides. At the time of the spring and autumn equinox, gravitation forces contrive to create the greatest tides of the year.

upon the gravitational pull of the moon and sun upon the ocean. This creates a tidal bulge that travels from the Atlantic into the Irish Sea and into the English Channel. Regardless of it being a spring or neap tide, when the peak of the tidal bulge (high tide) has progressed up the English Channel to Dover, the following trough (low tide) will be around Falmouth. Every month the full and new moon align with the sun maximising their gravitational pull, creating spring tides. As they move out of alignment the gravitational pull is reduced, creating a period of neap tides. At the time of the spring and autumn equinox, gravitation forces contrive to create the greatest tides of the year.

young and old tides

Other than at the times of the quarter moon, there is no definitive moment when a neap tide becomes a spring tide or vice versa. However in sea angling terms, the spring tide is the dominant tide and the period leading up to it, be it from the waning gibbous of a new moon the or waxing crescent of a full moon, both are deemed to be young tides—a tide of growing energy and exuberance, exciting and drawing the Bass inshore. As the spring tides fall off it is said to be an old tide, which sees the Bass move offshore into deeper water, only to repeat the cycle on the next young tide. Again this is a local phenomenon; around the shores of Portland the age of the tide begins and ends at 1·8m.

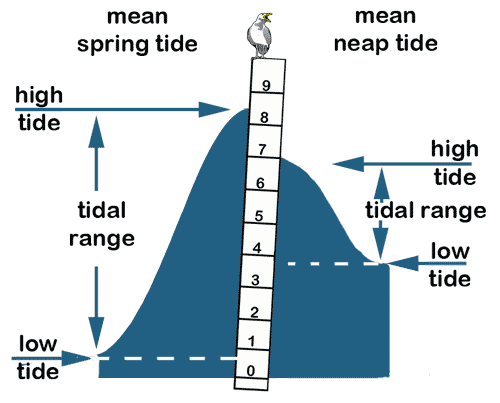

tidal range

Because the height of the tidal bulge upon the seashore is dependent upon the shape of the coast and topography of the seabed, it differs from port to port. A tide board identifies this constantly changing measurement. In the image, the zero (chart datum) and the nine represent the lowest and highest astronomical tides. The mean spring tide range is the average height of the highest lowest spring tides, the same applies to the mean neap tidal range.

tidal anomalies

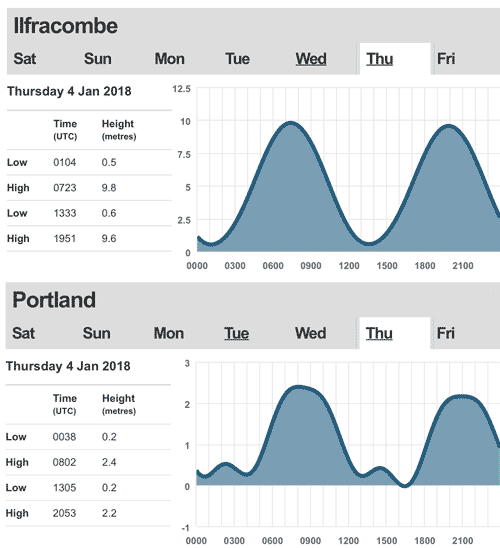

These graphs from the BBC tide page show how tide  predictions differ from place to place.

predictions differ from place to place.

The Ilfracombe graph shows the early flooding tidal range is 9·8—0·5 =9·3m, the later tide is 9·6—0·6 =9·0m. The changing height of the tide is shown to be a classical growing and diminishing wave with little standing water at the crest or trough.

In contrast the Portland graph shows a double low water that at one-point creeps below the datum, which is not that unusual. Whilst the tidal range on that day is only 2·4m, discounting the troughs and peaks, there is little difference between the tidal streams.

When using the BBC tides page run the mouse along the edge of the wave to see the height of the tide at any particular time. Also see the National Oceanography Centre page for tide tables or the Tidetimes page for monthly tables. All of these sites give lots of other useful information.

Variation.

Tidal range varies from place to place. In the Severn there is a rise and fall of over forty feet (12m) at springs, whereas in Scotland there is a place where the rise and fall at such times is less than four feet (1.25m). The average, however, is between ten (3m) and twenty feet (6m) at spring tides.

The shape of the coastline causes many freak effects with tides, and due to the Isle of Wight splitting the "tidal wave" as it moves up Channel, Southampton has four tides every twenty-four hours instead of two. The rise of Southampton as a port is, in fact, largely due to this, for ocean liners require plenty of water.As you move around the coast from south to north, the time of low spring tides will differ. Around the south-west coast they always occur at about midnight and midday, whereas in Scotland they come in early morning and late afternoon.

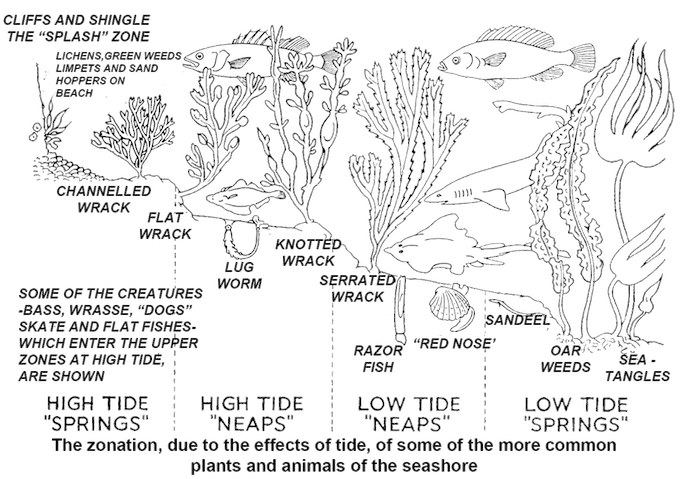

Tidal Zonation.

One of the studies of ecologists have long been concerned with the zonation of animal and plant life on the shore and rocks. All sea creatures are profoundly under the effect of tide—the tide brings life; the tide can bring death. All shore animals and plants have to adapt themselves to daily changes, and in consequence we find them seeking those levels on the shore that best suit their particular requirements.The sea is ever a place of extremes, and the small periwinkle is one sea creature that is able to withstand long periods of exposure. This creature lives high up on the shore where occurs the "splash" zone. It is here that only occasional rough seas and exceptionally high tides will wet the rocks and cliffs—yet life exists even there. At the other extreme lives the cockle, which is seldom found above spring tides, or at least near the lower limit of neaps.

There is no clearly defined line that marks the end of one zone and the beginning of another; rather is it a progression from one to the other. However, even if a rough sea throws creatures up the shore, they will soon return to their natural habitat when conditions permit.

But what has this to do with fishing? Well, it certainly shows one small facet of life on the shore, and indicates the vast store of knowledge waiting to be gathered together before we can hope to understand fully the habits of the fish we seek.

Fish, being more mobile than other creatures on the shore, will move inshore with a rising tide, and there feed on the more sedentary and permanent inhabitants —for here there is abundant food at all times. So it is that the wrasse will move inshore with the tide, and browse with its strong teeth on the barnacle clusters, or take a prawn that is hanging head down under the weed. Flatfish will move inshore to feed on the now covered lugworm beds, and bass will seek and follow the inshore migration of prawns. As the tide covers the rocks a host of creatures come slowly up the tide-line, and depart again with the ebb.

The zone that is richest in life is that near the limit of low springs where the great tangles of seaweed abound. Here in the jungle-like holdfasts of giant weeds is food in plenty, and the larger fish come to seek and take their prey from the smaller species feeding there.

Zonation is important. If we are prepared to spend just a little of our time studying the habits of the shore life, we shall be richly rewarded. If we "just go fishing," we may well miss something that helps to make our sport all the more interesting—and miss something that will help to pass the hours of waiting that so often occur before a bite.

Tides in Rivers.

In most rivers, the rising tide brings fish in from the sea. These fish, such as bass, pollack, and flatfish, will begin to move up-river as soon as the tide commences to flow, so the angler fishing near the seaward limit of the river can expect to get fish before the man fishing five miles up-river. With a boat it is possible to follow the course of the fish through a single tide, catching them all the time, whereas the fellow on the rock will find his fruitful fishing time confined to a matter of one or two hours.

Tides create pronounced currents in a narrow river, and fish will often be found in the quiet water behind out-jutting rocks, whilst others prefer the rapid-flowing water. It is as well to remember that the fish in the sheltered water will remain there for a long time, whereas those in the current flow are passing quickly. This makes all the difference where a shoal of bass is concerned, for instance, for once in the quiet water they will often remain there for some time, feeding on the life that collects in such places.

The ebb-tide sees the return to the sea, and at low water there is frequently a short spell of inactivity when the fish will not feed.

Tides on Beaches.

A rising tide slowly covers the lugworm beds, and the shellfish extend their siphons to feed, whilst crabs and sand-eels come out of the sand. Thus a rising tide provides ample food for fish and a great attraction for them to move inshore and feed. If a rising tide corresponds with a rough surf, then the disturbance caused by the waves will release vast quantities of food and provide an excellent opportunity for the shore angler.With an ebb-tide the reverse happens. As the tide recedes down the beach, more and more of the possible food goes into protective retreat, whilst many creatures actively move out into the safety of deeper water.

Whilst fish can be caught at all states of a tide, there is little doubt that the most suitable time is a flood-tide.Tides on Rocks.

The most common fish food associated with rocks is the prawn. It is now known that prawns migrate offshore with the ebb-tide, and thus by the time the tide is low all the prawns will be out in deeper water. In consequence, the fish will be there feeding on them. As the tide rises, the prawns again move inshore and—most important—keep coming. Following this food supply come the wrasse and species that feed on them.Always try to fish a rising tide over and off rocks, for then your chances are at their highest. From place to place conditions do differ of course, and that is one more reason why local conditions must be studied.

Time and time again we have observed the truth of the inshore movement of fish during the flood-tide, and there can be little doubt that tides have a profound effect on fish movements around rocks and reefs.Tidal Flows.

Wherever tides are constricted by flowing between rocks or deflected by headlands, the currents will be most pronounced. When the sea bed is also shallow, this tidal effect will be most marked.To fish one of the tidal flows often proves rewarding, for the small fish and sea creatures are carried along in the current, followed by the larger ones.

Finally, the value of keeping records is stressed. Jot down the time fish began to feed, etc., and then, later, you can always check the state of the tide. In this way you can soon learn the best times to fish a certain location, and you will always find that even if "time and tide wait for no man," the fish always "wait for the tide."

Time and Tide.

There is a time, coincident with certain states of tide, when most sea fish feed really well. That time supreme is dawn, and the angler who can be at his fishing place before first light can be sure of good sport.

Get to know your own locality—discover the state of tide when you get most fish; note the species. Then choose a day and go after that particular species when its favourite tide comes at dawn.You will get more fish during the two hours after first light than the rest of the day. There is no doubt whatever that time and tide are important—but it is up to the individual angler to discover the best combination in his own locality.